In this Easter edition

Save the date: Friday 9th of May: Books & Booze

Message from the board, by Ammerins Moss-de Boer

Julia Kühn: Literature is always political, by Marjan Brouwers

It’s a mystery: The Poirot Paradox, by Reinou Anker-Sollie

Unforgettable books: We need to talk about Kevin, by Elke Maasbommel

A double portion of Romeo & Juliet, by Monique Kroese and Janny Boers

In Memoriam: Wil Verhoeven, Mary-Jo Arn and Nico Robat

Taking a walk on the Wilde side, by Ammerins Moss-de Boer

A cozy afternoon in early Spring, by Marjan Brouwers

Save the date: Friday 9th of May

Join us for a thoughtful and engaging discussion of Normal People, the bestselling novel that captured hearts (and broke a few) around the world. Sally Rooney’s quiet, powerful story follows Connell and Marianne—two complex, intelligent characters who navigate love, friendship, class differences, and miscommunication from their school days in a small Irish town to university life in Dublin.

We’ll talk about the novel’s themes—intimacy, identity, power, and emotional vulnerability—as well as Rooney’s unique writing style and the quiet intensity that’s made this book a modern classic.

As always, the Books & Booze session will take place in Walter’s Bookstore from 17:00 – 19:00. You can sign up here or by using the QR code below.

Message from the board

by Ammerins Moss-de Boer

It’s April First, April Fool’s, and I am currently on the train, en route to an interpreting assignment. I am quite proud of the fact that I have not having fallen for any jokes yet – which was quite easy as I was the first one up, the first one out of the door and only limited my reading to the newspaper headlines before putting on a podcast (Tangled, highly recommended!). However, in the current political climate, even the headlines and real news can seem like a joke, so maybe I’m getting fooled left right and centre.

What is no joke, is our Spring Anglophile. We have tried to compile an interesting read for you again, that will hopefully be able to draw you into a world of make belief and talented writing. I think that all of us in the Alumni Club can agree on the fact that books are our happy place, the ultimate escape, even when the world we are escaping to is scary – I only have to think of Prophet Song that is still on my bedside table – in which case they help us deal with the horrors that we encounter in the outside world in a safe manner, giving us (new) coping mechanisms or just a good excuse for a cry.

On a happier note: what do we have for you this time?

We have an interview with the new professor of Modern Literature, Julia Kühn; the first instalment in a series on detectives and sleuths; an article about discovering the Wilde side of London; and another Unforgettable Book. Also, you can read more about events past (the March Books & Booze and the performance of Romeo & Julia in Diever and our April get-together) and future (the May Books & Booze). We also include three obituaries as, very sadly, in the past months we lost three lecturers who taught at the RUG English Department. Their lives deserve to be remembered.

Again, we hope to see many of you at one of our future events. Keep on reading and keep your shoelaces tied!

PS: Can I also ask you to put 22 April in your diary? Our Anglophile editor Marjan Brouwers will then be presenting part 3 of her dystopic book trilogy: Anderland. Info can be found on her website: https://leegland.nl/anderland-komt-uit-op-22-april/

Introducing Julia Kühn, professor of Modern English Literature and Culture

Literature is always political

By Marjan Brouwers

Just over a year ago, Julia Kühn accepted the chair of Modern English Literature and Culture at the English Department. She came to us from the University of Hong Kong, where she was Professor of English Literature. Originally, Julia hails from Germany and holds Master’s degrees from Bonn and Oxford Universities, a PhD from London (Birkbeck College), and she completed the Habilitation at Bamberg University.

So, how did the University of Groningen convince such a distinguished professor to join the English Department? ‘Circumstances,’ Julia replies. ‘I was happy in Hong Kong for twenty years. And then, unfortunately, China basically steamrolled over Hong Kong. All of a sudden, we ran into freedom of expression issues. I ran an annual literary festival and our donors started to make a fuss. We were no longer welcome in particular venues, because one of our writers was considered a dissident. Things became iffy with the national security police after 2020. Although I was teaching and researching 19th-century literature, I realised that all literature is about ideas of freedom, the individual, about equality, equity, class, race and gender. Literature is always political. And so, there was a political dimension to my leaving. At the same time, my husband and I had ageing parents back in Germany and France. It was time to leave.’

A love match

At first, Julia worked as a visiting professor in Provence for a time, which took her away from teaching in Hong Kong. ‘I had a wonderful time in exile and then head-hunters found me and asked if I would be interested in applying for this chair in Groningen. And I thought: you know what? Groningen is halfway between Berlin and Paris. That would be amazing. We’ve always loved the Netherlands, both of us, so it just became a natural fit.’ She was interviewed for the position in Groningen in February 2023. ‘The job sounded challenging but I came in with a lot of administrative experience. I had been head of school for three years in Hong Kong and associate dean of teaching and learning for seven years. And, then, I met the chair group and they were simply amazing. We ended up talking for three hours and I almost missed my train back to Paris. It felt like a love match, so I said yes.’

The joy of teaching

Teaching in the Netherlands is a new experience for Julia. ‘I loved my students in Hong Kong, but there was a lot of rote learning. In Dutch society, there is more space for free thinking and creativity. I find the students over here incredibly creative and inventive. It’s quite challenging to teach first years because they are so engaged and creative and they will call me out if say something they don’t agree with. I love that! Especially in the first year, we need to challenge our students, so we should not shy away from difficult topics or controversial interpretations. We need to give them the basics of English literature: the tools they need to break out of those moulds that we have taught them. So we want them to be slightly out of their comfort zone, because otherwise there’s no upward trajectory into years two and three.’

Don’t confine yourself to one academic interest

Julia’s academic interests are not confined to one subject: to the contrary. She recommends everybody to have at least two. ‘For me, it is the Victorian novel on the one hand and travel writing through the ages on the other, so anything from the Odyssey to contemporary travel writing. So, I write about Jane Austen, Mary Shelley, George Eliot – my 19th-century go-to person -, Dickens, Thackeray and Trollope, but also about travel writers. It’s such a pleasant genre because it’s creative but factual at the same time. It really lives in that space between documentation and imagination. Whenever I’m sick and tired of the Victorian novel, I turn to travel writing and vice versa. So, you know, I say to my PhD students: develop two legs to stand on, and I’ve said it to my junior colleagues as well.’

The importance of writing drafts without turning to AI

One of the topics Julia is concerned about is the upsurge of artificial intelligence. ‘So, students are all using Grammarly now to check their spelling. That is not cheating; I am okay with that. But the next step is students using ChatGPT to write an analysis of Catherine Earnshaw in Wuthering Heights, for instance. I don’t think students intend to cheat. It is often a matter of utter panic that makes them turn to AI tools. They ran out of time. They had issues at home. They broke up with a girlfriend or boyfriend. They were sick. And then they panic and turn to these artificial intelligence options. Now, it is our job to teach students why it is so important to go through the process of writing several drafts. I always tell them that I had to write my first PhD dissertation chapter seven times because my supervisor, Isabel Armstrong, a marvellous Victorian scholar and poet, looked at the first draft, put it in the bin in her office and said, you can do better. I wrote the second draft. She said, let’s improve on this. I learned that you need several drafts to get where you need to be. It takes time to notice connections or really understand what a text means and what to write about it. To be sure, it is hard work. Students need to realize that as well. Creativity is also doggedness, going through draft after draft. It is important for students to see that too.’

Dealing with dreadful budget cuts

Looking back on her first fifteen months in Groningen, Julia admits things didn’t quite work out the way she had expected. ‘I won’t lie. When I accepted this job, nobody expected having to deal with the budget cuts we are now facing. When I started this job, we were going to expand. A lot of money was coming in through the so-called sector plan, and new positions had been created. I was really glad about this, because in my eyes, it meant there was political and institutional faith in the importance of the humanities. And then, the government changes and all of a sudden, we’re being told at all levels, in all faculties, you need to cut. I didn’t think that I was going to come here and do curriculum work because I had done it for seven years in Hong Kong and hoped I could focus on research with my chair group, build research centres and attract more PhD students. But the experience, for better or worse, that I’ve had in Hong Kong for seven years is now coming in handy, because I have seen so many curriculum reforms over the years. And so we are making the best out of a bad situation. We streamline our curriculum where we can, without losing the contact hours with our students, without losing the learning objectives, which are critical thinking and communication in speech and writing. I truly believe in the importance of language learning. But it’s expensive, because you need a lot of contact with the students, and the more time we have, the better thinkers and writers they become. We can’t put 150 students into a lecture hall, like some scientists can. Our teaching is one one-on-one or in small groups. So the budget cuts are hurting us a lot. And, considering the governmental threats to internationalisation, what is really important at the end of the day is ethical thinking and diversity. I continue to believe in the idea and the ideal of global citizenship. It is paramount that our students learn to respect diversity and otherness. And so we’ll do what we can, even with budget cuts, to keep those ideas and those ideals going. They are now more important than ever before!’

Embedded in society, doing our job

It angers her when people say universities are elitist and against the people. ‘We’re not unique in the Netherlands. Look at North America, look at Britain. Everywhere there’s this fear of expertise and this false discourse of elitism. We are as embedded in society as anybody else. Our aim is to make society better. We’re not in an ivory tower, sipping sherry in our offices and talking at elevated levels. We are really talking about deeply human values of tolerance, empathy, morality that we then take into the community to make this world a little bit better; one discussion or book at a time. When people say that literature is a luxury or is elitist, I get really furious. Literature is about sympathy, empathy, and teaching you to see the world through another person’s eyes. The big problems of the world can’t be solved by scientists alone. The arts and humanities are as an important component in solving the problems of the world, and the future is for scientists and humanities to sit down and work together.’

It’s a mystery!

The Poirot Paradox

by Reinou Anker-Sollie

Did you know, that Agatha Christie got fed up with her own creation, Hercule Poirot? She called him “a detestable, bombastic, tiresome, ego-centric little creep” and ‘offed’ him as early as 1940 when she wrote the book Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case? I didn’t know until recently, but I think I can understand how writers can tire of a character. But Agatha, lucky for us, had a lot of common sense and realised Poirot was way too popular to die, people adore(d) him, and well, she earned money with him, so the actual death of Poirot was postponed until her own life was nearing its end (published in 1975). However, not liking the character she invented herself, might not have been the main reason why she wrote about his death in 1940, because she did the same for Miss Marple. It seems like she tried to do the public a favour and wrote an ending for these two detectives, thinking she might not survive the Blitz of WW II.

Where Agatha had a love-hate relationship with Poirot, I grew up with Poirot, with the (Dutch) books I discovered on my brother’s bookshelves and also with David Suchet representing him on television. (Click here to find out How David thought about Poirot, fast forward to 4:11 for the important bit). I deeply admired the detective for his intellect and therefore excused him for being, well, eccentric. I guess the outsider in me could relate to him, as Agatha Christie went above and beyond to make him an outsider. And as I am writing this article, I’ve come to realise that many popular “detectives” are outsiders: brilliant but socially different (rude, awkward, etc), so I will dive into that a bit as well, but first Poirot!

What do we actually know about Poirot from Christie’s books?

🕵️ Full Name

Hercule Poirot – His first name, Hercule, reflects his French Belgian heritage and is likely a nod to the mythical Greek hero Hercules, though Poirot’s “strength” is mental, not physical.

📍 Nationality

Belgian – He is a proud Belgian and often corrects people who assume he’s French.

🧠 Occupation

Former Belgian Police Officer, later a Private Detective.

He often references his past experience with the Belgian police force, particularly in the Brussels police (usually called the “Police Judiciaire”).

📏 Appearance

In The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Captain Hastings describes Poirot: “He was hardly more than five feet four inches but carried himself with great dignity. His head was exactly the shape of an egg, and he always perched it a little on one side… The neatness of his attire was almost incredible; I believe a speck of dust would have caused him more pain than a bullet wound.”

In addition he is immaculately groomed, especially his large, stiff, waxed moustache, which he takes great pride in maintaining. And he is always dressed in formal and neat clothes, often with gloves, spats, and a cane – even in casual situations.

🧼 Personality Traits

He is meticulous and extremely orderly. He dislikes dirt, disarray, or any kind of mess. He relies heavily on his “little grey cells” (his mind) to solve cases – he emphasizes logic over physical clues. He speaks in formal, sometimes broken English, often sprinkled with French phrases (e.g., “Mon ami,” “Mais oui!”). And he is polite but vain, especially about his moustache and intellect.

Character Development on Screen

What occurred to me is that considering the number of works featuring Hercule Poirot: 33 novels, 51 short stories and 1 play, we know quite little about him! David Suchet had a list of 96 little one-liners about the detective, but that mainly consists of mannerisms, like how many lumps he drinks in his tea of coffee. And therefore I completely get why Poirot interpretations on television and the big screen have added personal details about him that cannot be retraced in Christy’s novels.

The latest film, Death on the Nile, produced by Kenneth Branagh, especially surprised me. The film opens with a World War I sequence where a young Poirot, serving in the Belgian army, devises a successful strategy to advance his company. However, during this manoeuvre, he sustains severe facial injuries from a booby trap explosion. While recovering in a hospital, his fiancée (OMG a fiancée!), Katherine, suggests that he grow a moustache to conceal his scars. The film also delves deeper into Poirot’s personal life, portraying him as a more melancholic and romantic figure, which adds layers to his character which as perhaps necessary in order to speak to a larger audience in current society. However this also caused a mixed reception of the films: Some viewers appreciated the added layers to Poirot’s character, finding that the exploration of his past and personal vulnerabilities made him more relatable and provided a fresh perspective on the classic detective. Others felt that the introduction of a tragic backstory and romantic elements strayed too far from the original portrayal of Poirot, who was traditionally more enigmatic and less emotionally exposed. Additionally some critics argued that the film’s focus on Poirot’s personal history overshadowed the central mystery, leading to a less engaging whodunit experience. In my personal opinion Branagh went overboard where character development and fidelity to the source material were concerned. But I liked the film nonetheless, so I would recommend it to you all!

Character Development in the Books

You could argue, that if you grow tired of a character of your own creation, you could let him develop, and grow. Now, since Poirot was already retired when Christie started writing about him, changes in his character were limited, but throughout the works some behavioural changes are visible. ChatGPT kindly listed them for me:

🕵️♂️ 1. Early Poirot (1920s – 1930s): The Methodical Outsider

🔍 Behaviour: Logical, emotionally detached, very much the outsider — almost a caricature of himself.

🧩 2. Middle Poirot (late 1930s – 1940s): The Psychologist

Poirot becomes more nuanced in these years. He still solves mysteries with his intellect but shows more understanding of human nature and psychology. His cases get more layered, often involving moral dilemmas and tragic outcomes.

🧠 Behaviour: Begins showing empathy and respect for the emotional aspects of crime.

👤 3. Late Poirot (1950s – 1970s): The Morally Complex Figure

In novels like Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case (written during WWII but published in 1975), Poirot becomes a much more complex, even dark figure. He wrestles with moral questions, especially when faced with the idea of “preventative justice” (in Curtain, he takes a highly controversial action to stop a manipulative killer). He is increasingly reflective and aware of his own limitations — and aging.

⚖️ Behaviour: Less focused on ego, more driven by justice — even when it challenges the law.

I asked ChatGPT to do this for me, because I have never read the books in a chronological order and couldn’t possibly do this myself. Perhaps I should reread them😉.

Relationships: The Inner Circle

Readers of the Poirot works will have noticed that Poirot is not romantically involved. He even seems to view emotion, particularly love, as a distraction from logic. But there are a few characters in the books that he has some sort of a relationship with, because all good detectives (seem to) need an inner circle to explain (or perhaps boost about) how they solved the mystery.

Poirot’s Watson is Captain Arthur Hastings. Hastings is loyal, brave, but often gullible. Poirot calls him “mon ami” and enjoys having him to explain his reasoning to. I would like to add that in the Poirot series with David Suchet, Hastings is quite an attractive character and also quite the ladies’ man, which spices things up a bit and brings with it a pleasant airiness for the viewers.

Then there is the actual police, or in Poirot’s case, Scotland Yard’s Inspector James Japp. Inspector Japp works with Poirot, especially in the early stories (The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Lord Edgware Dies, One, Two, Buckle My Shoe) and he is much more pragmatic and gruff than Poirot, but he comes to respect his methods. Their interactions often include friendly bickering.

There is also George, Poirot’s Valet, who serves Poirot in several stories (The Mystery of the Blue Train, After the Funeral). He shares Poirot’s appreciation for neatness and order. And his calm, almost stoic demeanour form a quiet support presence in Poirot’s household.

Miss Lemon is Poirot’s secretary, appearing in several novels and short stories (notably Hickory Dickory Dock, Dead Man’s Folly, After the Funeral). She is described as efficient to the point of perfection and she never makes mistakes, except once, which Poirot notes with alarm. Her passions are filing systems and order, which aligns with Poirot’s love for neatness and method. Theirs is a professional but respectful relationship. Poirot appreciates her precision and loyalty, and she tolerates his eccentricities.

Where George and Miss Lemon seem to perfectly match Poirot’s lifestyle, and Hastings and Japp complement him in a business (and sometimes) personal capacity. There is another frequent character that seems more interesting, to me at least:

Ariadne Oliver is a mystery writer who often complains about her fictional detective and the writing process and she is a clear reference to Agatha Christie herself. She and Poirot collaborate in several cases (Cards on the Table, Mrs. McGinty’s Dead, Dead Man’s Folly) and their friendship is quirky and respectful — she’s chaotic and impulsive, which contrasts wonderfully with Poirot’s rigidity.

Is Poirot One of a Kind?

Now I have noticed, as mentioned above, that the classic detectives have an inner circle, confidants, or side-kicks. People who are trusted, even when they might be connected to a crime. This is quite common for the genre Poirot falls under. To my opinion, the characters surrounding the detective definitely bring colour to the stories. Technically, these characters are often used to serve both narrative and character purposes: Confidants help the detective “think out loud” so readers/viewers can follow the reasoning and they often reveal more about the detective’s personality through contrast or commentary. Being a fan of the genre, I can’t help myself and mention a few other famous our well known detective that bear great resemblance to Poirot. You might (or might not) have come across them already in books or on television. I have to admit that I saw most of them on television first and started reading the books later. But that’s a positive thing right?

Sherlock Holmes, created by Arthur Conan Doyle, is the most famous one. Sherlock uses pure logic and deduction. He often disdains physical evidence in favour of mental reasoning. He is detached, brilliant, and highly observant. He has a side-kick, Watson, whom he considers to be his friend, but Sherlock is colder and less sociable than Poirot, however he is methodologically similar.

Adrian Monk created by Andy Breckman in a TV series called Monk (2002–2009). Adrian has many Poirot-like traits: He is a brilliant detective with obsessive-compulsive tendencies who uses his psychological insight to read people. His character is emotionally complex, but often underestimated due to quirks. The difference with Poirot is that the extreme attention to order and cleanliness is even more extreme than Poirot’s.

Father Brown created by G.K. Chesterton is not a professional private detective but a priest, however he does manage to stick his nose into thinks the constabulary thinks he should butt out. But his priesthood does allow him to talk to people in a completely different way. Father Brown is soft-spoken, modest, but deeply insightful. He uses intuition and moral understanding to solve mysteries. In this he focuses on human nature and spiritual motivations and he solves crimes others miss due to his empathy and insight. Thus Father Brown carries much more empathy than Poirot does, but they both use the little grey cells to solve mysteries.

I would also like to mention Benoit Blanc from the films Knives Out (2019), Glass Onion (2022). Southern drawl aside, Blanc is a modern Poirot: polite, eccentric, and razor-sharp. He solves cases through close observation, interviews, and psychological reading. He has a flair for drama and enjoys explaining the solution in style.

And, although I could go on and on, there is one recent detective I have encountered that I think is worth mentioning and that is Cordelia Cupp. She is the central character in the (Netflix) murder mystery series The Residence. She serves as a consulting detective for Washington, D.C.’s Metropolitan Police Department and is renowned for her exceptional observational skills (she’s a birder/twitcher) and unique investigative methods. In The Residence, Cupp is summoned to the White House to investigate the murder of Chief Usher A.B. Wynter during a state dinner. The case presents a formidable challenge, with 157 suspects spread across 132 rooms. (You can watch the trailer here). Despite the complexity, Cupp’s relentless pursuit of truth and her ability to notice details others overlook make her the ideal investigator for such a high-stakes case. Her distinctive personality and unconventional methods instantly reminded me of Poirot! (Fun fact about the White House and the series can be found here: but this contains spoilers!)

The End

At the close of this article, I would like to mention a final fun fact about Poirot. In Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case, he dies at Styles Court – the same place where his first case occurred (full circle). This book was published in 1975, just before Agatha Christie herself died (in January 1976). Interestingly, Poirot received an obituary on the front page of The New York Times on August 6th, 1975. He is widely considered to be the only fictional character to ever have received such an honour.

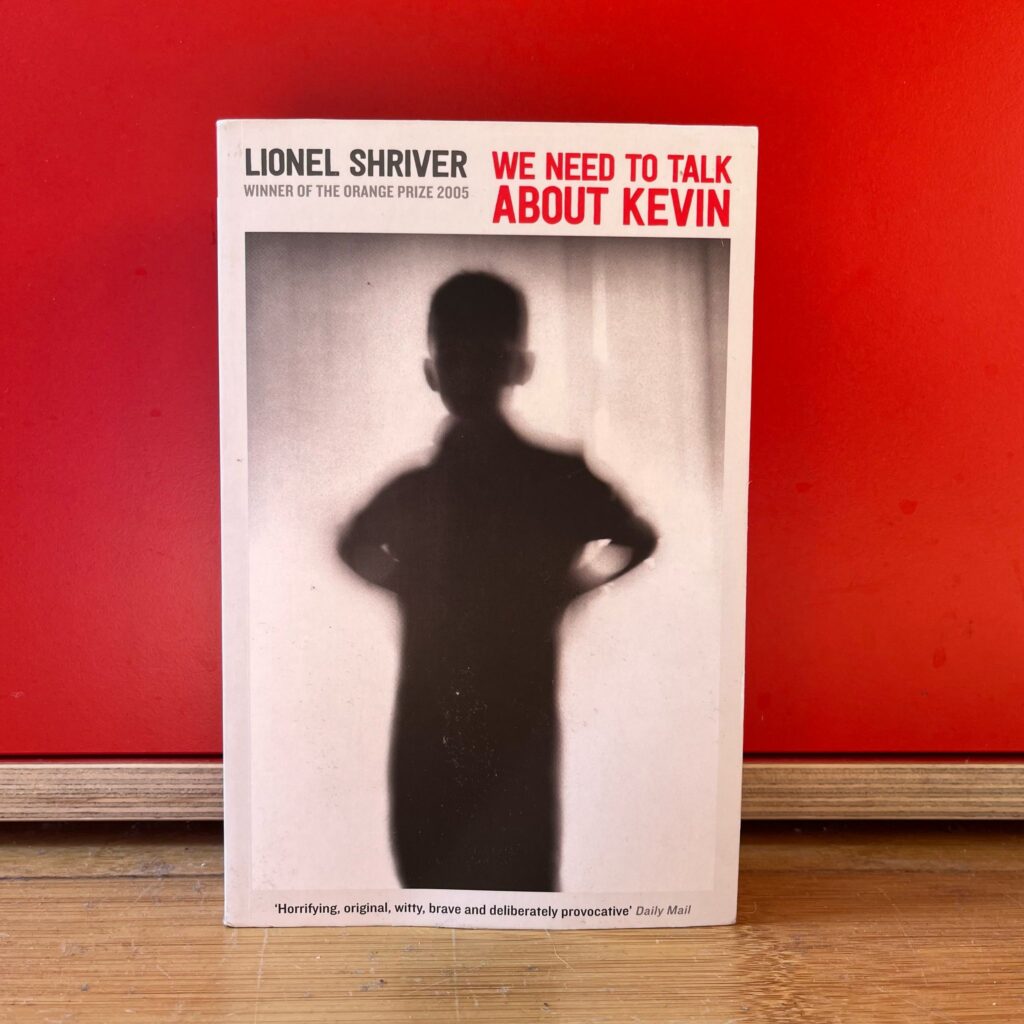

Unforgettable books

We Need to Talk About Kevin, by Lionel Shriver

by Elke Maasbommel

Fiction can change the world. Recently, the success of the Netflix series Adolescence, about a young boy who kills a girl after he’s been influenced by the so-called “manosphere”, led to fierce debate in the British House of Commons on whether they should impose stronger regulation on social media. We should ban social media, we should pay more attention to misogynist content, and parents should check in with their children more often – everyone’s talking about real-world problems inspired by a tv-series. But this is not the first fictional foray into this dark topic.

Years ago, a novel with a similar plot was published, and it’s time we return to it. Published in 2003, Lionel Shriver’s chilling We Need to Talk About Kevin was inspired by the US school shootings in the 1990s. It’s written from the point of view of Eva, the titular Kevin’s mother, who tries to figure out what made him kill several classmates and a teacher. Needless to say, that answer is never given. More interestingly, though, it explores the notion of culpability and the idea that parents might have seen it coming – and because it focuses on Eva rather than Kevin, it also shows how parents might respond to such a gruesome event.

For gruesome it is. I know people who claim they haven’t read the book (or watched the movie) because they could not handle the subject matter. Somehow, this is every adult’s worst nightmare – and of course this makes sense. Not only do we imagine the horror of everyone who’d be affected by such a dreadful event, but some of us also wonder what it would be like if someone we knew, or even worse, our children, turned out to be murderers. Obviously, this is something we’d rather not think about.

Still, every once in a while, we should. With mass shootings still happening on an almost daily basis in the United States, and the manosphere and their misogynist messages gaining more and more foothold in both the online and the real world, we should acknowledge this is a problem that will not go away by itself. Tv series like Adolescence and novels like We Need to Talk About Kevin remind us of those uncomfortable truths, and we can’t look away from them.

For about fifteen minutes after the final scene of Adolescence, I found myself unable to speak. I remember feeling the same when I had finished We Need to Talk About Kevin. After this initial silence, however, I felt the need to talk about it. For talk about it we must.

That’s because fiction can change the world.

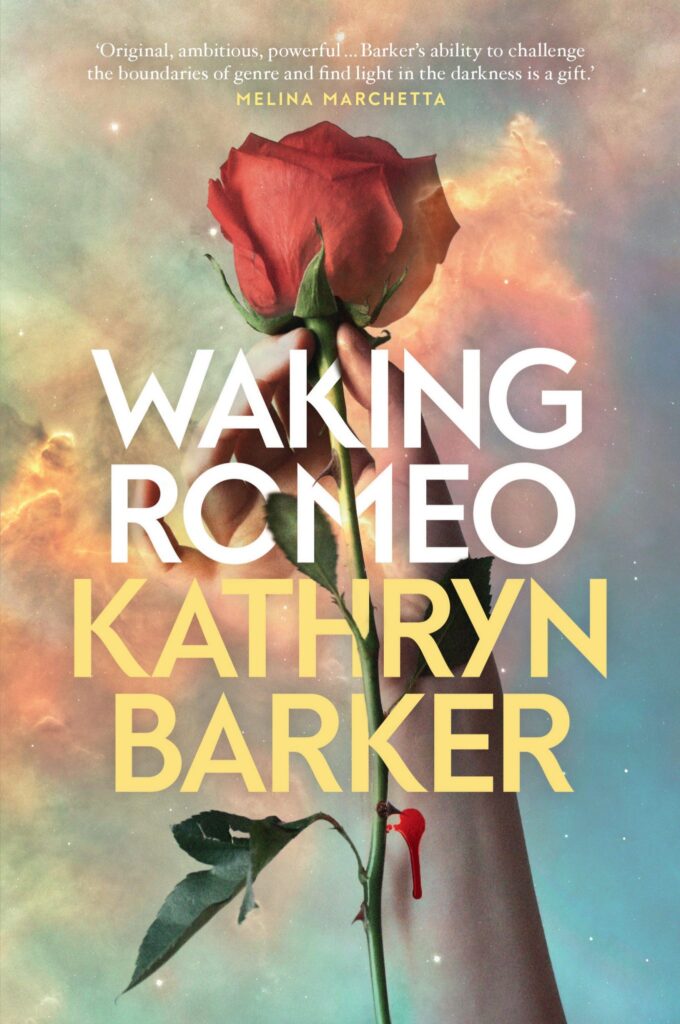

A double helping of Romeo & Juliet

First, while enjoying delicious cocktails, we discussed the YA novel Waking Romeo, then, the very next day, about twenty of us gathered in Diever to see the Romeo and Julia version of the Diever Shakespeare Theatre troupe. Monique Kroese wrote a review of the novel and Janny Boers sent us a text about how she felt after watching the play for the second time.

Books & Booze, 7 March 2025. Kathryn Barker, Waking Romeo

By Monique Kroese

Once more, the booze was excellent. The four cocktails matched the themes of our selected reading very well. In the words of Elke, cocktail master together with Ynze: “Juliet & Romeo: very modern an feminist, placing the female character before her male soulmate, a variation on the classic Gimlet. Part-time Lovers: you can’t love somebody with your entire body and soul if you’re not exactly shooting in and out of their timeline. Williams: powerful, elegant, complex, layered, like Shakespeare himself always was, still is and always will be. Shirley Temple, a mocktail: Juliet was only thirteen years old when she became one of the most famous literary characters ever; no booze for her.”

“For never was a story of more woe, than this of Juliet and her Romeo,” ends Shakespeare’s play. What if … Enter ‘Waking Romeo’ by Kathryn Barker. A time-travel novel. Dystopian. Young-Adult fiction. The main characters are Juliet (Jules, these days) and Ellis (Heathcliff’s surname). Never mind the time difference between them, time-travel is the story’s vehicle after all.

The book starts in the year 2083, when the world as we know/knew it has ended and the only way out is forward. For most people. It moves back to 2056, forward again to 2083 and 2107, ending in 2084, one year after Jules, having survived her attempted suicide, has woken Romeo from his coma. The book is divided into five Acts (Roman numbers indeed) and some 53 very short chapters, alternatively told by Jules and Ellis. In their various accounts and reminiscences, Jules and Ellis refer to yet different times and years.

Both Jules and Ellis have a mission: Jules is estranged from her family after the affair with Romeo, and decides to sit with him every day, dreaming about him waking up from his coma and their reunion. Ellis is sent on a mission that he has been preparing for but he doesn’t know what it is or the reason why until things start moving. Waking Romeo from his coma turns out to be their shared goal, albeit for different reasons. Ellis is educated and guided by a robot with a long-term vision, Jules discovers all by herself what a twat Romeo actually was. Does this sound confusing?

For me it was. I kept trying to understand who was who, what they were doing where, how their time travel worked and most of all, WHY? Reluctant to start all over again, I decided after about one-third of the book to accept my confusion. I kept on reading. Not that my questions were all answered when I had finished the book, but at least I had tried to make sense of it all.

The questions for discussion, prepared again by Elke, helped me to make more sense of the book. It also made for a lively discussion. The detective work (what themes, contemporary issues, which other plays by Shakespeare, what other references) was part of the fun at the meeting. For example, we identified multiple themes: action versus inaction, the love of literature, rewriting your own story, personal responsibility and our relationship to time and love. The nod to Taylor Swift as announced on the cover was not found by any of us. Maybe we were not Barker’s intended YA readers, the youngest book lover present being an impressive 26 years old?

And unlike Shakespear’s tragedy, Barker ends on a hopeful note when Jules writes: “I turn back to Ellis. And I come full circle.”

Everything is reversed

by Janny Boers

Romeo and Juliet wanted to marry against their parents’ will in Shakespeare’s original play. In this adaptation, Paris and Rosalinde go against her mother’s will by refusing to marry each other. Everything is reversed. In both versions, it does not end well when parents try to impose their will on their child or when children resist their parents’ will under the guise of love. Love cannot be forced. And meanwhile, love does exist, but it doesn’t fit the patterns of expectation. I liked the play even more now that I saw it for the second time ! Good night everyone !

In memoriam Wil Verhoeven and Mary Joe Arn

In January we received the sad news that two former staff members of the English department had passed away. Since it took some time before we would publish this Anglophile, we decided to post their obituaries on our website. You can find the obituary about Wil Verhoeven here and the link to the obituary of Mary-Jo Arn here.

In memoriam: Nico Robat (1935 – 2025)

By Marjan Brouwers

On the third of March 2025, Nico Robat passed away in Groningen, at the age of 90. He was known at the English Department as an excellent lecturer of linguistics as well as a passionate drummer, playing in several jazz bands for years.

As a lecturer, he was known for his lectures about grammar and syntax. He was co-author of A Student’s grammar of English (1984) and Points of Modern English Syntax (1975). In 1988 he showed his interest in computer science in his publication On Developing a Sentence Analysis Program: A Progress Report.

Robat studied in Leiden, graduated in 1961, and joined the English Department in 1971, where he stayed till the early nineties. He was part of the Linguistics group. In 1983 he wrote about his work as a lecturer in the Icebreaker, the student magazine of English in those days. Reading his account of a week in the life of a teacher, takes one back to the previous century, only to find out that things have not really changed. For instance, Robat writes about the difficulties allocating tasks among staff members and how to balance teaching and research with administrative duties. Also, he wonders why students dislike oral exams and prefer written ones. He shows understandable irritation when he arranges an extra lecture to make up for a lost one and only two students turn up.

In the early nineties Robat retired, which gave him more time to spend with his wife and children, his music (he performed as a drummer in several bands, well into the noughties) and of course taking his dog for long rambles.

Taking a walk on the Wilde side

By Ammerins Moss-de Boer

Okay, London, here we are again! I visit the capital at least once a year for educational, language immersion purposes *cough*, and I try to discover a new part of the city every time. London allows you to travel the world simply by getting on a different tube – and the city itself is only a train journey away*. But what do you do when time is limited? Even though I had five full days in London, I had to somehow cram in two days of conferencing (CIOL Translators Day and Interpreters Day), one day at the London Book Fair, five plays and (of course) various bookstores to pick up some books from my to-buy list.

This left no time for leisurely, long strolls through museums to try and decipher runic inscriptions or a belly-busting high tea with a view, and I even ignored the Touristy Big Five (Big Ben, Westminster Abbey, Number 10, Buckingham Palace, the Tower). However, I did want to experience a bit of city culture, so I opted for a concise journey of rediscovery of an area I know all too well, but seeing from a different perspective: that of Oscar Wilde.

I am not ashamed to admit that I am currently neck-deep in my Oscar Wilde Era (it overlaps heavily with Taylor Swift, as the pins on my bag will show), and I have great plans to translate some (or all) of his plays (and maybe even the novel) into Frisian. I don’t know how much Wilde is being taught at Uni these days, but it is amazing how topical his work still is, despite it being well over a century old. His plays, fairytales and prose contain scathing criticism of society and the hypocrisy of the well-to-do, and although of course we no longer live in a world where women ‘come of age’ when they turn 23, and no ward needs the permission of their guardian to get married, still: the similarities of how we impose our values on people who are different, are striking. One of the plays I had on my London list was The Importance of Being Earnest, a joyous little play about confusion, ambition, parentage and, of course, true love. Unfortunately, it was not on “live”, but it was being shown in the cinema, and to be honest… if you are in the front row, it is almost better than in an actual theatre. The HD was almost too real at times. And watching Sharon D. Clarke and Ncuti Gatwa (yes, the Doctor!) almost pop out of the screen was an experience I had not wanted to miss.

But I digress. Oscar Wilde. Most people will know him for the Earnest play and for his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (or one of the various film adaptations), and of course his lifestyle, which eventually became his downfall. Wilde loved everything opulent and extravagant, definitely lived outside the box, and was one of the first real “influencers” as we now call them. He was caricatured, derided and ridiculed, but sales of sunflowers, lilies, health powders and cigars went through the roof. And where better to live the dandy lifestyle than in Bloomsbury, London? (Until he was outcast and exiled, of course, but that is another walk.)

To follow in Wilde’s footsteps, I took a walking tour with VoiceMap**. While walking the streets of Bloomsbury, I listened to the narrator (Blue Badge tour guide and interpreter Brian Cookson) talk about Wilde’s tragic life, loves and literature. It was a great way to explore an area I know well (last year, I followed a literary tour, with Orwell’s Ministry of Truth (University of London) and some very ugly busts as its highlights…), but Cookson led me into a few side streets and arcades, and pointed out buildings and plaques that I had always just walked by. And really, what is wrong with my sense of direction, that I never realised that St. James’s Palace is so close to Piccadilly…? Maybe because I always approached it from The Mall…

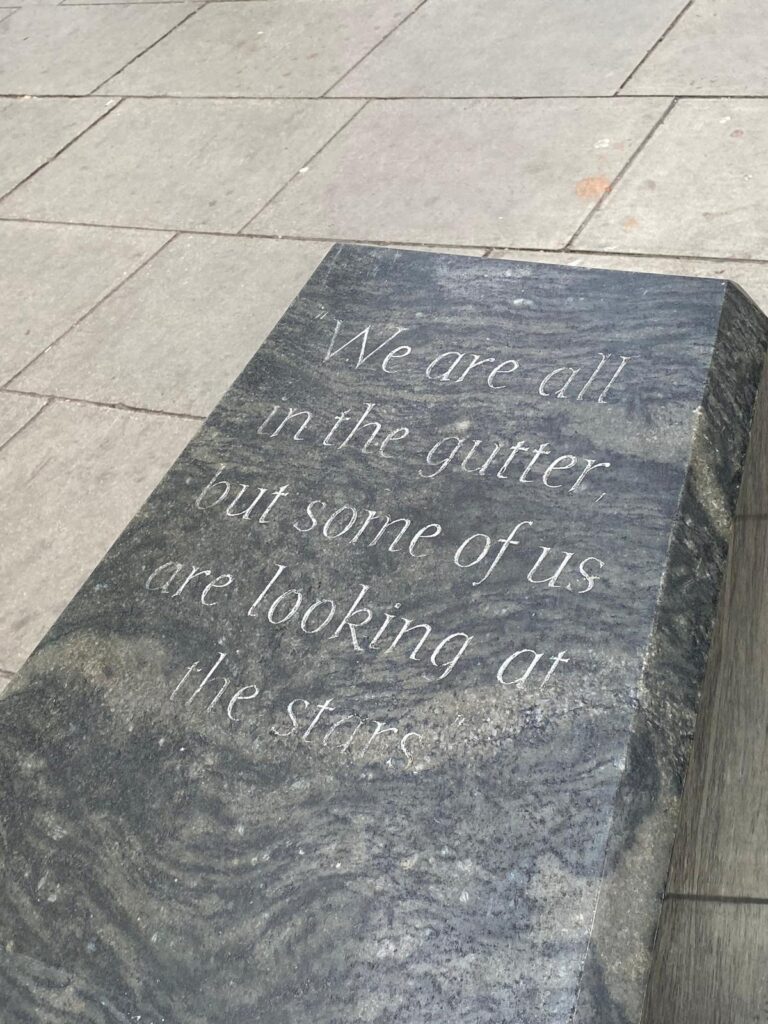

I paused the tour at Hatchard’s, where the table where Wilde actually signed his books has pride of place (and of course, I bought some Wilde here), and stood pondering at Haymarket Theatre (where several of his plays were put on) for quite a while, debating whether or not I was going to add a sixth play to my trip, and even considered going the extra mile and book the VIP treatment so I could see the Oscar Wilde Room. In the end, I just stood there, admiring the architecture, sighed, and walked on to the statue of Wilde behind St. Martin-in-the-Fields. There you can read a quote from his play Lady Windemere’s fan that we can all take to heart: “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars”.

And that is what I did later that night, walking back to my apartment from the Globe, past the Shard: I looked up at the stars and thought back to one of the first times I came across Wilde. It is amazing how things come full circle… When I was in Belfast doing my Master’s, I attended the premiere of Wilde, with Stephen Fry playing the author. I shook Fry’s hand, mumbled a few words about being so honoured to meet him and wrote a glowing review for the cross-community newspaper I was volunteering for. The movie hurt, it was raw, it felt so unfair to be persecuted and prosecuted for who you love… and there we are, hey presto, in today’s world – where nothing seems to have changed.

So, to end with another quote from Wilde, from Dorian Gray: “Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without being charming. This is a fault. Those who find beautiful meanings in beautiful things are the cultivated. For these there is hope. They are the elect to whom beautiful things mean only Beauty. There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.” Ergo: read more books!

* Please don’t forget to get your ETA if you are travelling to the UK!

A cozy afternoon in April

by Marjan Brouwers

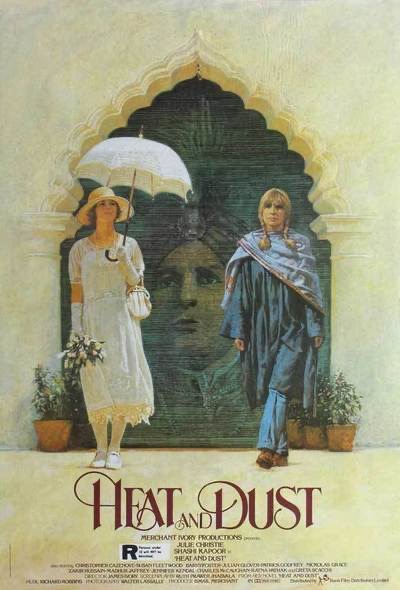

For this annual get-together the board selected a wonderfully bookish venue (Literary cafe De Graanrepubliek), and invited lecturer Pauline Mc Gonagle to speak about her fascinating research into the fiction and literary archives of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, who was a novelist as well as a screenwriter. She was responsible for the screenplays of famous films like Remains of the Day, Howard’s End and A Room with a View.

Most impressive was Pauline’s story about how she opened a large number of boxes containing Ruth’s personal letters, first drafts and other valuable documents. These boxes had not been opened for decades and had been sealed by layers of cloth. Her lecture was so interesting that I ordered a second handcopy of Ruth’s best known novel Heat and Dust (winner of the Booker Prize) right away.

After listening breathlessly to Pauline’s fascinating lecture, we trooped down the steep stairs to get some refreshing drinks and prepared ourselves mentally for the second part of the get-together: a party game, not involving a murder this time, but the search for someone spreading nasty gossip about everyone in the room. This ‘Bodgerton’ mystery kept us busy for the rest of the afternoon. Finally, we left the Graanrepubliek, found out the weather was still lovely and decided to have dinner outside.